Climate preaching, the proposal that consumers should voluntarily and individually protect the climate, induces a feeling of guilt that elicits climate denial and the observed reluctance to communicate the problem —climate silence. It is argued that climate preaching is therefore overall detrimental. The implicit induction of guilt and its rejection is a major reason for difficulties to communicate on climate change. The argument is exemplified by the story of Ignaz Semmelweis, the pioneer of evidence-based medicine who was born exactly two hundred years ago.

Preface

There are two reasons for writing or reading this article: Its arguments are important —if they are acknowledged. So far, nobody has written about them with consequence, as far as I can see.

The observations described and the thoughts presented in this text were collected and have matured over decades. However, the contemplation of existing results from scientific work and the writing of the text took less than one year.

The text was made available online in an early stage, then expanded considerably, resulting in a medley of arguments and much repetition. To improve on this, it was structured in four parts.

In Part One I summarize the tragic case of science denial of the 19th century. It caused the death (in agony) of millions of childbearing women. The title reflects the relative importance Semmelweis‘ story had in early versions of the article. If the title were chosen anew, it would rather be ‹the guilt complex on climate change› or similar.

In Part Two I point out the similarities between the rejection of Semmelweis‘ findings and the denial of climate change. There are several good books and many articles that explain the primary cause of climate denial, the deliberate deception led by the fossil fuel industry.

This article addresses the question why it was so easy for the deception campaign to spread doubt and disbelief. Why, for instance, do so many join in to spread doubt without being financed by big coal, big oil and gas? The induction of guilt, the avoidance of the unpleasant feeling and the psychological rejection of implicit accusations are key to understanding our difficulties to communicate on climate change.

In Part Three it is argued that appeals to consumers to voluntarily reduce their carbon footprint are guilt-inducing implicit accusations and therefore contribute to denial as well as to our reticence to talk about global warming. These two negative consequences of the appeals alone should be reason enough to refrain from appealing for individual consumer action.

The proposal is new, perhaps original, at least in this degree of thoroughness. Not everybody will find the proposal to refrain from climate appeals immediately compelling. Ultimately, the inevitable question is this: Should climate preaching (as I have decided to call the proposal of voluntary individual consumer action) be done and encouraged or should it be abstained from, discouraged and rejected? As so often, the answer to this question could be: it depends.

It depends on the audience addressed, one could claim with good reason. True, not everybody is affected by the appeals in the same way. However, the appeals reach everybody. In the end, we cannot really select our audience. To preach or not to preach on climate change, that is therefore the ultimate question this article addresses.

There may be more reasons to reject or welcome appeals for voluntary individual acts than the preaching’s negative effect on denial and climate silence. This is also discussed in the rather consequential third part of the article. There may, however, also be positive impacts of climate preaching.

In Part Four it is argued that the net effect of climate preaching is negative because possible positive effects are too small to compensate for the appeals‘ negative effects. Even, the supposedly positive effects may in fact rather be negative effects.

Perhaps, I should point out that I excluded one variant or outcome in my considerations. (Or, maybe I should not point it out because the outcome is extremely remote.) Whether the net effect of climate preaching will ultimately be negative or positive depends on how humanity will cope with carbon emissions —or continue to fail to contain them.

If there is continued failure to put effective policy in place to stop CO2 emissions but, instead of policy, a further development towards declaring and considering personal consumption resulting in carbon emissions a moral sin; if, consequently, a corresponding new moral belief becomes universally accepted and complied with, like a strictly followed religion, then climate preaching would be positive. It is a nightmarish scenario. To solve the climate crisis would take a long time —if it wouldn’t virtually take forever.

Consequently, the effects of climate change would be devastating. I am not sure who would have to be blamed for it, the climate preachers or those who fail to act politically on climate change by being a responsible politician or by putting pressure on politicians. Yet, the climate preachers, their followers and those who don’t act politically are often the same people.

To treat climate change as a personal, moral challenge, not a societal, political challenge, is a welcome subterfuge to escape our real responsibility. It is an excuse to dodge the need and effort to address the problem of climate change effectively, in due time. The psychology described and decried in this article serves to justify these excuses.

My arguments may psychologically be difficult to absorb. Their importance should nevertheless be recognized. The labeling of the text as «opinion» and the inclusion of some personal anecdotes are not meant to undermine the weight of the presented claims.

As particular as my claims and concerns may appear, I am not all alone with them. Albeit scarce, some existing research as well as books and articles by climate communication specialists already strongly support my initial claims (made in the second part). Also, friends and specialists commented positively on drafts and early editions of this article, a piece that has become the size of a small book. However, some reactions (a peculiar reaction) also make clear that my arguments are not only welcome.

There is a hesitation to spread and accept the arguments presented in this article because the message won’t likely be liked. Paradoxically, the acceptance and deployment of the arguments are hindered by essentially the same problem the article itself describes. The text may be perceived as an accusation and its arguments are therefore not likely to propagate with ease.

To accept the importance of the «guilt complex on climate change» one must be ready to view climate preaching with a critical eye and even view voluntary individual consumer action critically —at least to some extent. For many, this is very difficult, psychologically.

As in the case of Ignaz Semmelweis and his colleague doctors, those who should embrace my arguments most eagerly, or at least should take them into unbiased consideration, are also the most likely to feel offended. It can be anticipated that many will find the arguments personally inconvenient, qualify them as unjustified assertions, consciously or subconsciously perceive them as accusations and reject the arguments before giving them due consideration.

However, be assured, this piece is not meant to be an accusation. It is meant to help solve a problem. I can only hope that readers, specifically climate communicators, will read with an open mind. I wish they consider both the hypotheses and the supporting research and will find them helpful for their work and our common cause. Nearly everybody should be a climate communicator, but only few are.

Introduction

A personal account of denial

It was around 1978. I was busy spray-painting my kayak, when someone pointed out to me I was also busy destroying the ozone layer. It could be read in the newspapers, she said. I did not immediately believe her. For a moment I had fallen victim to what is defined below as the accusation rejection bias.

They won!

The government of the US, the world’s most powerful nation, both militarily and economically, has been taken over by climate (science) deniers. As if this alone were not terrible enough: They were elected democratically. This success by science deniers is unprecedented.

The takeover happened more than 150 years after the radiation property of carbon dioxide, which is responsible for its greenhouse effect, was first measured in a laboratory and more than one hundred years after the effect of augmented atmospheric CO2 concentrations was first quantified and predicted on the geophysical level —by mere brainpower, paper and pen.

Caveats also occurred: Oceans will take up CO2. Absorption bands of water vapor and CO2 overlap. Clouds fully moderate greenhouse gas induced warming; aerosols do; etc. These caveats indicate a psychological pattern, a desire to discover a bright side of the situation and communicate it. The caveats were nevertheless all dispelled.

Thirty years ago, James Hansen made precise predictions and testified before the same congress that is now dominated by outright deniers.

We now experience the unequivocal confirmation of old, essentially undisputed science. The global average temperature ventures into a realm never experienced by human civilizations. Unless effective political action is taken, it will, in the foreseeable future, increase to degrees never ever experienced by any creature of the genus homo.

We are witnessing the first devastating irreversible effects of greenhouse gas induced warming and CO2 in the oceans: the destruction of coral reefs, the ecosystems on which much if not most of the diversity of life in the oceans depends. Unless effective political action is taken, tropical corals will, in the rather near future, be gone.

The deniers won. Maybe they won even more than their originators wanted them to win. The sides are divided and continue to get polarized.

At least for now, the deniers go stronger than ever and the other side is largely paralyzed. While all this happened and happens, there is a strange silence. Politicians, neighbors and even scientists are reluctant to talk about climate change.

Why is that? What has gone wrong?

It is overdue for climate communicators to thoroughly analyze our difficulties, our approaches to communicate the problem, to rethink our acts —and readjust.

→ Jump to part 2 – Impact of Guilt Induction and Guilt Avoidance on Climate Communication

Part 1 – Semmelweis‘ Challenge

Remembering Ignaz Semmelweis

August 13 should be highlighted in every climate communicator’s agenda. With his name, Ignaz Semmelweis epitomizes the first important case of denial of modern science. Like the denial of climate change, it had devastating consequences. It cost the lives of millions of mostly young women who died in agony.

The denial was due to the same psychological factors that now cause the denial of climate change.

Semmelweis was a victim, too. Disregarded and vilified he, too, died in agony; on August 13 in 1865, in the Landesirrenanstalt Döbling, an asylum for the mentally deranged near Vienna.

Ferdinand Hebra had lured Semmelweis to Vienna to commit him to the asylum where Semmelweis was put in a straitjacket and a darkened cell. Hebra was a leading capacity in his field, dermatology, and one of Semmelweis‘ teachers in medicine. As the editor of the Viennese medical journal, Hebra had announced Semmelweis‘ breakthrough discovery in obstetrics (the branch of medicine that treats childbirth) and had given it due acclaim. The document which, seventeen years later, attested Semmelweis a mental disease had been signed by János Balassa, Semmelweis‘ house doctor, an internationally recognized authority in plastic surgery and a pioneer of cardiac resuscitation.

An autopsy of Semmelweis‘ body was carried out by Carl Braun, who succeeded Semmelweis at the maternity clinic of Vienna’s Allgemeines Krankenhaus only a few years after Semmelweis‘ landmark discovery. Braun was Semmelweis‘ nemesis, both in Vienna and later in Budapest. By then, Semmelweis had few friends among obstetricians. (Braun and Hebra were awarded the honor of knighthood in 1877, at a time when germ theory had proven Semmelweis right.)

Multiple bone fractures were inflicted upon Semmelweis, supposedly by his guards, when he was forcefully delivered to the asylum. The fractures were neither reported by Braun nor by anyone else of his time. They were revealed a century later, in 1963, following an exhumation of Semmelweis‘ bodily remains. The mistreatment was not responsible for Semmelweis‘ death, however.

Ironically —or perhaps perfidiously— he was killed by an infectious disease, similar or even essentially equal to puerperal sepsis, also known as childbed fever. It remains unknown whether the infection was accidental or deliberately inflicted. The prevalence of inconsistencies around his death supports the hypothesis that Semmelweis was murdered.

The degree, nature and cause of his mental illness also remains unclear. An advanced state of syphilis or Alzheimer’s disease are being hypothesized among other candidate illnesses. It also remains unclear to what extent ignorance, indifference and rejection had made Semmelweis lose his mind.

Vienna’s Allgemeines Krankenhaus was among the leading hospitals for medical treatment and research. In an attempt to contain infanticide —or perhaps rather prostitution— women were urged to give birth in hospitals.

Admission to the obstetrics clinic was free of charge for the pregnant. Nevertheless, pretending to not have been making it to the hospital in time, many preferred to bear their children in the street. Their chances of survival were much higher if they stayed clear of hospitals, where often one in ten mothers died in their childbed. The death rate could be twice as high, during months.

From at least ancient Greece onwards, until Semmelweis‘ time, medical wisdom was dominated by the belief that an alleged equilibrium of four bodily fluids was key to the health (and temperament) of a patient. Failures of the theory were systematically excused by the pretense that every medical case was as individual as was the patient.

The advances by Louis Pasteur and others still lay a couple of decades in the future. However, in Semmelweis‘ time as a doctor in Vienna, medical practices and knowledge had already progressed beyond mere superstition and false excuses for shortcomings.

- The existence of transmitting diseases was well accepted.

- Vaccinations with cowpox against smallpox, invented in China in the 16th century, were applied widely.

- Decades before Ignaz Semmelweis‘ discovery, the Italian Agostino Bassi had proven with experiments that a microscopic «vegetable parasite» —a fungus, really— caused a disease in silkworms which in turn devastated the French silk industry.

- Semmelweis wrote about the similarity —and difference— of contracting diseases transmitted directly from one person to another and the indirect transmission he discovered. Albeit not yet declared, and far from explained, germ theory was in the making.

Three years before Semmelweis‘ discovery, US American physician and writer Oliver Wendell Holmes had already strongly proposed that puerperal fever could be transmitted via doctors, their hands and instruments and that hygiene was key to the prevention of the disease. He did not focus on hand hygiene as much as Semmelweis. But he was also confronted with the dismissal and rejection of his findings, essentially for the same reason.

Charles Meigs, another US obstetrician, who objected Holmes stated that doctors were gentlemen and gentlemen’s hands were clean. That was in 1854, 10 years after Holmes‘ and seven years after the initial publication of Semmelweis‘ findings. Meigs also objects Semmelweis (as «Semmelweiss»). His book is a compilation of examples to suggest doctors were not guilty of spreading puerperal fever. 1

Meigs explicitly rejects the implicit accusation of having himself been an agent of transmission of puerperal fever: «[…] I certainly was never the medium of its transmission.» 2

Unlike Semmelweis, Holmes did not let his adversaries take control of his life, made his point and moved on. Despite the opposition, his conclusions were known in Britain and, somewhat ironically, when Semmelweis stressed the importance of hand hygiene to prevent contagion with puerperal fever, his claims were rejected also under the pretense that they were not new.

Chloride of lime, which Semmelweis would advocate, was long believed to have disinfecting effect, including against puerperal fever, as is evidenced by an account from 1829 referenced by Meigs. 3

Autopsies were standard practice for post mortem diagnosis or to instruct medical students, which also indicates that medicine was busy moving towards scientific scrutiny.

And autopsies, Semmelweis revealed, were an essential part of the problem. After having tested and rejected at least two very different hypotheses, he identified a deadly cycle that killed about one hundred thousand women per year in obstetrics clinics —and would keep killing them for at least two more decades, despite Semmelweis‘ discovery.

It was common practice for students or doctors of obstetrics to examine the body of deceased. Without properly washing their hands in between, they could dissect the body of a woman who had fallen victim to puerperal fever and go on to examine the vaginas of pregnant women. With their fingers they recycled the disease from the dead to the living, sometimes to the yet unborn too.

Several factors helped Semmelweis identify the problem. The Vienna maternity clinic had two branches, one operated by doctors and students, the other mostly by midwifes. The pregnant women who were directed at the doctor’s branch of the clinic suffered and died from childbed disease significantly more often than those who were looked after by midwifes —who also refrained from vaginal inspections.

The two branches‘ different reputation made many women solicit to be permitted to the safer branch of the maternity and they sometimes cried in desperation if their wish was disregarded. (They were not given the choice.)

Another hint was the death of a pathologist, a dear colleague of Semmelweis. After having been wounded by a student’s scalpel during an autopsy, the pathologist contracted a fever and died. The symptoms of his disease and his dead body suspiciously resembled those of the women who all too regularly died in their childbed.

Last but not least, Semmelweis —unlike most of his colleagues— acknowledged that he himself was a major part of the problem.

A conflict with his superior, Johann Klein, helped him discover his own deadly effect. Semmelweis was not Klein’s protégé, to say the least. Perhaps, differences between the two sprang from Semmelweis‘ ambition as a scientist. Klein’s scientific ambitions flew low and he might have preferred to obstruct Semmelweis‘ career. Or, possibly, their opinions diverged over political issues. Whatever the reason was, in late 1846, Semmelweis‘ appointment was not prolonged and he, who had done most of the autopsies, had to pause.

As a consequence, deaths from puerperal fever in the men-run branch of the maternity clinic dropped to a few percent, the level of the branch run by midwifes. When, soon afterwards, in March 1847, Semmelweis was allowed back to work, autopsies resumed and death rates sprang back up to near record heights.

Semmelweis concluded and imposed that hands needed to be washed thoroughly in a chlorine solution between autopsies and vaginal inspections. Consequently, death rates from childbed fever plummeted. That was in May 1847, 18 years before Semmelweis‘ death.

He believed that traces of decayed material from the dissected bodies stuck to the fingers of the doctors and students. (Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria then infected the unfortunate women.)

Two years after his breakthrough at the hospital, his assignment was again not prolonged, definitely, this time. He was offered a minor position in academia but refrained from accepting it.

A German speaker from Buda, Semmelweis returned to Pest, disappointed. (The two parts of today’s Budapest were not yet united.) There he took an unpaid position as the honorary director of a minor maternity clinic. While the problem had been rampant before, under Semmelweis, puerperal fever was eliminated almost entirely in that clinic. But once again, he was disregarded, even vilified.

The story of success but disregard repeated itself once again, after he had been able to get a position at the university hospital in Pest.

He is now considered a pioneer of evidence-based medicine. However, several decades should pass between his achievements and the posthumous recognition of his work and his rehabilitation.

Why the rejection?

It is often claimed that he was ignored, treated with disrespect and even accused of wrongdoing because he attacked and offended his colleague doctors unnecessarily the longer they ignored his findings and recommendations. These claims are difficult to support, at least from his public communications. In his 102-page open letter to obstetricians throughout Europe, which he wrote in 1861, his tone is not extraordinarily offensive —compared to, for example, how Karl Marx, a contemporary of Semmelweis, wrote about his competitors in the same trade.

Rather, there is indication that Semmelweis sought to minimize the faults of his colleagues and weaken the accusation.

While Semmelweis claimed that all puerperal fever infections «from outside» could be eliminated without exception if strict hygiene were observed, he attributed residual cases of childbed fever not to transmission but to infection «from inside», as he called it. He claimed that a deadly material, essentially the same «decayed beastly-organic substance» («zersetzter thierisch-organischer Stoff») that he suspected were transferred from the sick or dead to the healthy and living, could also develop inside the victims rather than always having been brought about from the outside.

He suggested this way of «internal» infection even though there had been a long time at the Vienna hospital without any deaths from childbed fever, before autopsies were made. And there was an entire month without deaths from childbed fever, March 1848, when Semmelweis had temporarily succeeded to enforce a more rigorous hygiene policy: Doctors had to wash their hands not only after autopsies, but before vaginal inspections, too.

These periods without deaths essentially disproved the hypothesis of spontaneous internal development of the infection. It is hardly conceivable that this conclusion escaped Semmelweis. He nevertheless excused his colleagues from residual fatalities, when he probably should have attributed them to a lack of strict observation of his policy or generally inadequate levels of hygiene —the latter of which he also correctly believed were another way of disease transmission (open wounds, transmission via instruments, bed sheets, etc.).

Semmelweis was rather trying to find a way to excuse his colleagues than to accuse them for all fatalities from puerperal disease among their patients. (Semmelweis was nevertheless somewhat right with his suspicion of internal infection. The dangerous bacteria could be brought to the hospital by a pregnant woman with infected respiratory organs, but he could not have known about it.)

Either way, whether Semmelweis unnecessarily accused —as mainstream historic opinion posits— or whether he, as I found, had rather been seeking to avoid accusations: It is safe to say that for him the truth was more important than friendship and his social and professional environment. And, either way, whether implicit or explicit, his message war loaded with accusation.

Merely half a dozen authorities in his field supported Semmelweis. (One of them felt so deeply ashamed that he committed suicide after reckoning to have infected his pregnant cousin.) All other obstetricians ignored or rejected his findings, often vehemently. Yet, some of Semmelweis‘ most vocal critics, including his nemesis Carl Braun, discretely ruled out autopsies or vaginal inspections or strictly separated the two activities, with notable results, Semmelweis claimed. Many doctors knew Semmelweis was right, he pointed out in his open letter from 1861, but they did not admit it.

After having seen his achievements dismissed, Semmelweis remained rather silent. From 1858 onwards, however, he made another attempt to make his voice heard and published three books, including his main work, in 1861. It was also largely dismissed.

Naturally, it became gradually more difficult for Semmelweis not to appear being offensive towards his peers. At first the implicit message had been that they killed women inadvertently. As time went by and women kept dying, the implicit message inevitable became this: You keep on killing hundreds of thousands of women, knowingly. Semmelweis then also accused his colleagues explicitly, at least in closed letters.

Why is it so easy for the special interest groups working on behalf of the fossil fuel industry to make their voices heard and propagate denial, while climate communicators keep failing at their task?

Part 2 – Impact of Guilt Induction and Guilt Avoidance on Climate Communication

Reviewing the Semmelweis reflex

The «Semmelweis reflex» or «Semmelweis effect» is supposed to explain Semmelweis‘ failure to make his message heard. In Wikipedia it is «a metaphor for the reflex-like tendency to reject new evidence or new knowledge because it contradicts established norms, beliefs or paradigms».

However, this definition misses the main reason why Semmelweis failed to be persuasive. He had virtually had no choice but to accuse his colleagues. Even when he didn’t accuse them explicitly there was still an implicit but stark accusation, because the life of so many were obliterated.

Moreover, the accusation was linked to impurity, an accusation difficult for people to put up with psychologically. (It is almost a historical standard to vilify people by claiming them being impure; The «psychology of disgust and contamination» is considered to be an essential element of our moral foundation; Reticence towards hand hygiene in hospitals is still a big problem.)

There is a special element to Semmelweis‘ problem that goes beyond the biases that the current definition of the Semmelweis reflex suggests. (E.g. belief perseverance, an endowment effect for including non-material goods, the confirmation bias, the tendency to cling to an existing theory or worldview —and to reject a new theory or worldview, groupthink and belief in authority.)

This special element is the implicit accusation.

It would be sensible to redefine the Semmelweis reflex to incorporate the characteristic and probably determining aspect of Semmelweis‘ problem:

If a message, implicitly or explicitly, includes an accusation of the recipient, the latter is inclined to reject the message and has a tendency to accuse the messenger instead.

The rejection of the message and the tendency to raise a counter-accusation are two different elements of the suggested redefinition of the Semmelweis reflex. These two elements could be kept apart.

- The rejection of a message with an underlying accusation could be called accusation rejection bias.

- The tendency to accuse the messenger if the original message includes an implicit (or explicit) accusation could be called accusation reflection effect.

Semmelweis‘ problem was not so much the contradiction of «established norms», as the current definition of the Semmelweis reflex states. Much more, his problem was that, even though he did not say it like this at all, the message to his colleagues was inevitably heard like this: You kill women en masse by sticking your filthy fingers into their vaginas.

Who would want to perceive that? It is not surprising that Semmelweis‘ message was not well received.

The don’t kill the messenger saying proclaims the difficulties there are to convey an inconvenient truth. Semmelweis‘ message was far more troublesome than it was inconvenient. Even if implicit, it was a severe accusation. It is not surprising that his message was difficult to get across.

Distorted communication

There is another reason, a different reason, why Semmelweis gained little support. Not only did his colleagues not want to hear what he had found out, they did not want to tell it either. There is yet another psychological factor that aggravated Semmelweis‘ challenge.

It could be called implicit accusation inhibition to describe our reluctance to communicate fully or communicate at all, a tendency to communicate mildly or the failure to communicate correctly if the message includes an accusation, even if the accusation is implicit.

Psychologists found out long ago that humans rarely tell things as they are or that we are astonishingly reluctant to say what would have to be told in order to be honest. This is because the undisguised message is often not appealing to the people we communicate with.

We must always be worried about making friends and allies and not losing them. We therefore almost always carefully navigate between being honest to ourselves and the facts and avoid being offensive.

Not only our perception is full of biases that serve to please us. The active part of our communication is also biased. It is skewed to please the recipients of our messages in order not to disappoint or upset them.

The Semmelweis reflex as posited above, which stresses the element of accusation, and the implicit accusation inhibition are key to understanding important biases in climate communication.

Biased climate communication

There are various degrees of implicit accusation inhibition. In terms of climate change, they may be distinguished as follows:

- Climate silence (reluctance to communicate; not talk about global warming)

- Preference to downplay the importance of climate change, to discover and spread comforting, mild or positive climate information (lesser accusation messaging)

- Active climate denial (communicate incorrectly; actively question the existence of climate change, its causes or its effects)

These categories of the implicit accusation inhibition (A, B and C) are discussed separately in the following sections.

Climate silence (A)

Survey results for the United States should make us attentive. There is a strange silence on climate change. It is well documented and reported for the US. There is awareness of the problem and an organization which aims to counteract it. But, of course, the silence on climate change is not restricted to the US where people don’t want to talk about a problem they nevertheless want to solve (see video clip below).

«Americans believe they can solve a problem, even if they don’t believe we have a problem but they are not talking about it.» | Richard Alley in press meeting at AGU 2017 conference. Clip. Full video.

It has been tried to explain climate silence as the result of a spiral of silence, a mechanism related to groupthink, the tendency to align ones own opinion with mainstream opinion. To avoid isolation, those who do not adjust their opinion nevertheless keep quiet and thereby relatively strengthen the prevailing opinion, which causes a reinforcing feedback and elicits a spiral, the spiral of silence.

Groupthink, which is part of the spiral of silence theory, is a very important factor in climate communications and the perception of the problem, there can be not doubt about that. 4

The spiral of silence theory is compelling on its own and the theory is backed by observations. However, it falls short of explaining the silence among those who think climate change is real and should be addressed. And that is the majority, even in the US. Moreover, for the spiral of silence to start, there must be an initial inclination to reject the science of climate change, a widespread psychological inclination to not want to talk about it or an incentive not to talk about it.

There must be a different explanation for the observed silence, at least for its beginning. There is a psychological driver, a deeper cause for the silence. It is the implicit accusation inhibition.

We don’t want to talk about climate change with our neighbors, friends, relatives or peers —or voters (Germany, US 2012, US 2016)— because nobody wants to hear it, feel accused and guilty.

We neither want to accuse nor do we want to be accused. Even if there is no real accusation made, there is still fear that the climate message might be perceived as an accusation.

Astronomer and science communicator Harald Lesch alludes to the difficulty and reticence of communicating climate change because people just don’t want to hear about it. With his video answer a denier could hardly be more affirmative. At the beginning of a TV-broadcast to explain global warming, Harald Lesch asks: «How should I start?» The climate denier intercepts (blue panes): «Not at all! You already made a fool of yourself too much with your climate blabber and outed yourself as criminal climate liar.» «I keep repeating it, climate change is not an easy topic», continues Harald Lesch. The denier intercepts: «True, it is by now a repulsive, boring topic which JUST AND ONLY gets on people’s nerves because they can no longer stand hearing the rubbish and the lies!» Harald Lesch concludes: «In this way I began the broadcast and I said: ‚for heavens sake he starts [I start] talking about climate change again!‘, now here he also finishes his talk [I also finish my talk] with climate change.» «HOPEFULLY you finally finish with it and HOPEFULLY, you will be held responsible for your lying», intercepts the denier. | Compilation with beginning and end of a climate denier’s video based on a TV-broadcast by German ZDF.

The reluctance to talk to neighbors or friends about global warming is comprehensible. If we bring the topic up, we risk that their reply might be similar to this: «You also drive a car, fly, heat your home, use electricity or eat meat. Why do you talk to me about it?» People are unlikely to respond in this way. There is nevertheless much reason to believe they think in this way. And that is reason enough to keep quiet in the first place.

Intriguingly, Genevieve Gunther, who heads an organization, which is specifically devoted to end climate silence, is a climate preacher. In tweets she repeatedly criticized Leonardo DiCaprio for his flying. It is almost as if she were asking the superstar —one of too few to speak out on it— to shut up on climate change! Our urge to preach will be a topic in part 3.

Science is the method designed to elaborate the truth. We can expect communications by scientists to be more correct than average and I dare to claim that they usually are considerably more correct than average. However, scientists are also people with psychological biases. And even scientists cannot be perfectly correct.

Are there cases of implicit accusation inhibition or lesser accusation messaging in communications by scientists? There is reason to believe so. This will be the topic of the next section.

Lesser accusation messaging, scientific reticence and the least drama (B)

Implicit accusation inhibition may be the key reason for many climate scientists to be reticent to present inconvenient truths. This reticence was pointed out by James Hansen long ago. Climate scientists often err on the side of the least drama, other scientists explain.

A more recent case of lesser accusation messaging is the claim that we can allow for a lot more cumulative CO2 emissions than previously thought to stay within 1.5 degrees of warming.

To blame climate change on the sun is a classic of climate change denial. The rise of global temperature is clearly not due to the sun, as probably every climate scientist familiar with the topic would confirm. However, some scientists posit the sun might come to help in the future. It may be quality science, but —it remains to be seen—, it might be a case of lesser accusation messaging. Either way, of course, the deniers are happy to use the information to deceive the public (as is explained by Peter Hadfield). Earlier, but similarly, German denier Fritz Vahrenholt had received too much attention when he claimed the sun will help mitigate climate change.

A case of lesser accusation messaging has even gone mainstream among climate scientists. It is equally important as it is outrageous. Future generations, they assume or even suggest to rely on, will net remove massive amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere in the second half of this century (Joeri Rogelj here; UNEP there, page 50, tacitly cut-off at 2050 to hide the assumption of massive net carbon dioxide removal). As crazy as it may seem, this ill-fated assumption already serves to rate (underrate!) the compatibility (incompatibility!) of the countries‘ mitigation pledges with the temperature targets set in the Paris Agreement.

Almost ten years ago, climate scientists started to finally, finally, but still cautiously, explain to the world what they should have been shouting out loud for decades: That CO2 emission must be eliminated altogether —completely. They should, finally, tell the (not) ‚policy makers‘ that CO2 emissions must be cut now, right now, not later. But only a few reputed climate scientist dare to clearly hold this position and question the feasibility of massive net CO2 removal, as Stefan Rahmstorf does here. (As yet, nobody —as far as I can see— denounces the real Achilles heel of the belief in massive net CO2 removal, the missing political feasibility, the deficiency in global governance.)

The long reluctance to explain the need for a zero carbon economy and the claim that there will be significant net CO2 removal are both very consequential cases of implicit accusation inhibition — by omission or by misleading optimism, respectively.

Active climate denial as related to the implicit accusation inhibition (C)

There is a widely accepted taxonomy of global warming denial, established by John Cook and the team at Skeptical Science:

- Level 1: It’s not happening

- Level 2: It’s not us —or it isn’t CO2

- Level 3: It’s not bad —or CO2 isn’t

- Level 4: It’s too hard to solve

These levels differ in their degree of problem acknowledgement, but the avoidance of guilt is common to at least the first three levels of denial.

Consistent with the main argument of this section, among the very active deniers, the strongest rejection is on level 2: It’s not us —or it isn’t CO2! Climate denial often calls into question the effect of CO2, the greenhouse gas we all know we emit.

There is an extremely successful case of communication that removes guilt from the audience. Guilt removal is a central element of at least one world religion. The receptivity to messages that assert we are not guilty of causing climate change is not surprising. The temptation to suggest «not guilty!» or, a more adequate position for a scientist, to succumb to lesser accusation messaging, is huge.

Only very few true climate scientists reject the scientific evidence of human caused global warming. Typically, the opinion of the few deniers among the real climate scientists is that the human influence on the climate is smaller than what the overwhelming majority of climate scientists say. (At least the overwhelming part of the observed warming is man made; our best assessments suggest that all observed warming is anthropogenic or even slightly more than the observed warming.)

One of the few climate scientists who argue for a small human influence and a small rate of warming is John Christy (who declares to be a Christian). I believe that John Christy, as well as other scientists who question the human influence or consider global warming a minor problem, are driven by a desire not to feel guilty or are driven by a desire not to accuse their audience of being responsible for climate change.

You are not guilty, me neither

The preceding sections described how climate change is communicated in order to please the recipients of the messages and make the messaging psychologically palatable. However, by suggesting that the recipient is not guilty (or less guilty), the communicator also suggests not to be guilty (or less guilty) himself. It is difficult to say which psychological motivation, guilt removal from oneself or from the audience, is more important in a specific case. To try to deflect guilt from oneself is certainly an important contributor to distorted climate communication. It is discussed in later sections.

After having briefly treated climate silence, lesser accusation messaging and active denial, the following sections are about the receptive end of climate communication, the perception of the climate message and passive denial.

Induction of guilt and the perception of climate change

Almost everybody in the industrialized world drives a car, flies or buys stuff produced by means of fossil fuels. Virtually everybody contributes to CO2 emissions. The perception of the climate change message as an accusation is inevitable —at least to some extent—, even if no accusation is made explicitly.

«… running a bit hot!» Blatant accusation and self-centered impression management by nerdy activist. It rarely takes place between neighbors, and if the appeals are not very subtle, it quickly gets comical. | Video excerpt from Modern Family. Original)

Countless species will be driven to extinction by global warming and CO2 in the oceans, and that will be forever. For those worried more about human welfare, there is plenty of material to spot a strong accusation in the climate message, too. There is much reason to feel guilty.

There can be no doubt about the effectiveness and motivation of the professional ‚denial machine‘ with its sponsors in the fossil energy industry. However, both, the professional Merchants of Doubt and their sponsors might be driven not only by economic interest but a desire to avoid guilt by themselves and prevent accusations.

Despite the undeniable impact of deliberate deception by the fossil fuel special interests, this important question remains: Why is it so easy for the special interest groups working on behalf of the fossil fuel industry to make their voices heard and propagate denial, while climate communicators keep failing at their task?

It is because the public wants to hear that it is not guilty.

One important type of climate change communication, perhaps the dominating type of climate communication, was so far left aside: climate preaching, the stream of moral appeals to consume less or consume green or, more generally, the suggestion of voluntary personal carbon footprint reduction.

To approach the problem with climate preaching, let us first look at some examples of how the climate message, including the climate scientists‘ message, is received by the public.

A pattern in the rejection of climate science

There is a strange refusal to acknowledge the ‚human caused‘ part of the climate problem, but there is agreement to solve it. There is an easy explanation for this seeming paradox: We have plenty of reason to feel guilty about the cause of the problem. But nobody has a reason to feel guilty about its solutions.

Engineers should be particularly adept at understanding and appreciating science and physics. However, someone who did a lot to counter active climate contrarians once contemplated: «A typical denier is an engineer in his fifties.» Scientists confirm his observation. What engineers do in their professional lives almost always results in important CO2 emissions. Consequently, engineers have more reason than average to pretend not to be guilty. By denying the problem they avoid feeling guilty and try not to be seen as guilty.

The United States is the country of gas guzzling cars and super-consumption; the country with rampant per capita CO2 emissions. It is also the country of individualism, where government is vilified or marginalized, where individual responsibility is overstated and overrated. Climate denial is rampant in the US, too. The US as a nation and the average US consumer has exceptionally good reason to reject a feeling of guilt. Firstly, US emissions are particularly high. Secondly, American culture, like no other, posits individual responsibility, including for global warming. Consequently the individual feels the accusation and avoids it by denying the problem.

On the other side, people in countries that don’t much cause it, but rather suffer from global warming, are inclined to accept that climate change exists and that it is caused by human activity. Sometimes they even blame climate change to be at work where it isn’t. It is no coincidence that their perception of the problem is opposed to the perception of those who live in countries with high carbon emissions. They have the least reason to feel accused and guilty.

Nobody wants to feel guilty. One way to avoid a feeling of guilt is to deny the problem altogether. If global warming is acknowledged, it should not be CO2 (because that would mean me).

Intriguingly, the same psychology is at work with many climate activists who believe in self-centered action on climate change.

These activists almost systematically overestimate the role of methane as a greenhouse gas, compared to CO2. For any city dweller it appears to be an attractive proposition because, if methane is a main climate driver, cows or farmers are to blame. Furthermore, animal rights activists strongly influence the climate debate. Those who eat meat are at fault —not us. Have you ever wondered why vegetarians and vegans like the methane argument so much? To inflate the personal contribution they make by voluntarily abstaining from eating meat they distort the facts much like the sleekest and most stubborn of the climate deniers. The parallels between those who exaggerate their personal contribution (including with climate preaching) and the deniers are puzzling. The same psychology is at work with both groups and —one argument of this article—, the same emotion seems to be at work: guilt or the avoidance of it. 5

If you are often in touch with people who are environmentally concerned or even engaged in environmental action, including climate action, you notice something strange: Sometimes even they disbelieve that global warming is happening or that it’s caused by human activity. Can it be explained? I believe it can. There are essentially two ways to deal with guilt on climate change: Act or deny. Many environmentalists, I dare to hypothesize, are particularly susceptible to experience guilt, or particularly uncomfortable with the feeling, and use both methods to do away with the unwanted feeling.

Among environmentalists, there is widespread belief that forests remove CO2 from the atmosphere. They don’t. (Only growing forests do. But the potential of growing forests to undo our fossil fuel based emissions is far too limited, which should not be difficult to understand.) Many environmentalists nevertheless want to believe that, with time, existing forests will eventually correct our CO2 emissions altogether or they overestimate the potential of new forests to sequester and store carbon. A safe way to unequivocally be considered a climate hero is to start a tree planting initiative, although more forests don’t unequivocally cool the planet. (They do in the tropics but don’t in the Arctic, because forests alter the albedo.) The belief that trees will naturally —almost magically— undo what we do with fossil fuels comforts the mind.

A strange pattern of preaching and denial

An article by Michèle Binswanger with the title She leaves climate deniers fuming about Greta Thunberg, who broke ground with her climate strike, provoked more than 600 comments, most of them from deniers —as the article’s title proclaimed. The deniers express the motive for their denial. It is the reproach upon them that they emit CO2. «What did she do», one of them wrote, «fly to Poland to tell others that they produce too much CO2?» Another commentator opposed the deniers and pointed out that Greta travelled by electric car. Challenging the deniers, he added: «But it is always easier to criticize others than to do something yourself.» The deniers then calculated and posted the indirect CO2-emissions associated with Greta’s road trip to the UN climate conference where she spoke. (Why are the deniers so often worried about CO2 emissions, when these emissions are not a problem? But things get even stranger.) A denier responded:

«My current lifestyle and travel habits are probably almost exemplary in terms of CO2-savings for Swiss standards, I therefore have no reason to „criticize but not change“. Who just wasted energy to travel hundreds of kilometers to criticize others? My word: The girl. I hope you NEVER fly and live close to were you work, only use public transports or your own feet. If not, you’ll have much to catch up on.»

There is no reason for a denier to live a low-carbon lifestyle, but, as unreasonable as it may seem, deniers pointing out their own small carbon footprint abound. Actually, in the quote above, the climate denier is a climate preacher! He is not an exception.

There are many active deniers who are also climate activists, insofar as they limit their personal carbon footprint and brag about it. And there are many climate activists and preachers, including very active ones, who are also climate deniers. (I don’t know what you think about this, dear reader, but I think these two observations alone should make all bells ring loud and clear with everybody who seeks to understand climate denial.) In a way —think of it—, they are the same group. Anyway, they are motivated by the same psychology. That psychology serves to avoid a feeling of guilt and it serves the same ultimate purpose: dodge the work involved in engaging in real climate action to solve the problem. Could both, self-centered consumption-level climate activism and denial, be spurred by the same pieces of communication, climate preaching? In any case, the parallels are striking.

Before moving on to climate preaching and its guilt-inducing effect, we shall compare some other cases of science denial with the denial of global warming —in addition to Ignaz Semmelweis and puerperal fever from part one. There are more parallels to be drawn.

The parallel almost too terrible to mention

The Holocaust may not normally be compared to anything else. Its outrageousness demands exclusivity. In the Swiss parliament, Jonas Fricker recently compared the transportation of pigs to be killed in slaughterhouses with the death trains of the Nazis. He saw himself quickly politically lynched, including by members of his own party, the Greens, assisted by one popular newspaper (despite alleged regret, in the same bed). This happened although Fricker has no affinity with those inclined to belittle or deny the severity of the crime that the industrial killing on Nazi territory was. Within days of his controversial statement, Fricker resigned from his post as a member of parliament.

It may seem to be unrelated and, true, it is a little deviation, but, since I am here, it makes sense to report on it: On November 14, 2018 Jonas Fricker posted on social media: «Today, I start my personal experiment ‚finishing up with consumerism‘: From today onwards, for one year, I won’t buy any personal consumer article (…) Who joins in?» Another one is moving from political action to self centered action. Maybe, I should start a file to keep counting.

Journalist Peter Hadfield, who, as Potholer54, debunks climate denial like no other, abstains from calling climate deniers what they are («deniers»), because he deems the term to allude too strongly to Holocaust denier and doesn’t want the two kinds of deniers to be compared, associated or confused with one another.

It should not be necessary to state it. This section in no way aims at belittling the Holocaust committed under Nazi rule.

While the severity of the Holocaust should not be under debate, the severity of climate change lies mostly in the future and therefore remains to be experienced and judged about. To refrain from any comparison of elements of the Holocaust with elements of what is being done now would be wrong. For example, Adolf Hitler never visited a concentration camp. How did and does Donald Trump deal with the people of Puerto Rico before and after hurricane Maria? There is a huge difference between what was done under Hitler and what is done, or rather, is omitted, in the US under the current administration. However, these differences should not forbid the drawing of parallels between aspects of the Holocaust and aspects of other topics.

Another example: The complacency of high level politics and the general public in the face of global warming is reminiscent of the complacency by those who knew and should have known among the Nazi rulers and those under the Nazi regime —although, again, there are very important differences.

While climate change and the industrial killing in concentration camps are clearly not the same thing —that should go without saying—, there are parallels in the denial of climate change and the denial of the Holocaust, respectively.

Both cases of denial are supposedly improbable. They are both extremely strange. Both cases of denial should very clearly not be there.

The peculiarity of the denial of the Nazi concentration camps and the mass killings should not require much explanation. There are preserved camps, victims, survivors, liberators and other witnesses, interrogation protocols, testimonies, files with names. There are films and photographs, to mention the probably most amazing pieces of proof.

The peculiarity of the denial of global warming takes slightly more space to explain. The greenhouse effect of atmospheric gases was first theorized by Joseph Fourier in 1824. 36 years later, in 1860, John Tyndall measured the capacity of some gases in the atmosphere to absorb and emit long wave electromagnetic radiation. Only during these 36 years, more than 150 years ago, the atmospheric greenhouse effect and its consequence for earth’s surface temperature was truly a theory. In the 19th century, however, only few specialists were interested in the issue and the public abstained from the debate. If there was any debate at all, it took place a long time ago. When the greenhouse effect of the atmosphere became an acknowledged fact and ceased to be a theory, the public did not take notice.

When the changing climate due to its human cause was recognized —at least as a prediction based on emissions trajectories— the implicit accusation inhibition soon impacted the debate and temporary caveats against the warming effect of CO2-emissions appeared —consistent with the hypothesis of lesser accusation messaging.

However, these caveats were rather quickly moved out of the way (for example by Guy Callendar or Charles Keeling). Because there is only scant public awareness of the early transition global warming «theory» made from hypothesis to acknowledged fact, the fossil fuel industry succeeded in relegating it in the public domain to the level of a «theory».

If the evidence is as solid as it is for climate change or the Holocaust, there is not normally any denial anymore. This will become clear from the comparison with a historical, exemplary case of science denial.

Continental drift

For decades, there was a fiercely fought scientific debate over the existence, or not, of continental drift. The public took notice and participated in the debate. Evidence accumulated to the extent that the theory could at some point virtually be considered proven. In the opposing camp, many scientists and much of the public nevertheless clung to their old conviction and rejected continental drift theory.

However, when it was discovered that ocean crust is formed continually and new ocean crust displaces older ocean crust, which in turn shifts continental plates around, the debate over continental drift was terminated. Scientists now measure the amount of continental drift, which confirms and quantifies the effect of the discovered mechanism at work. These days, you don’t notice many still insisting that continental plates are immobile.

When there is proof provided for a theory, when the physics are revealed and understood, there is no longer any debate and the theory becomes an acknowledged fact. Unequivocal results from reproducible measurements that provide proof of a theory normally terminate any debate around a scientific issue. At least, that is what could be expected. Not so with the denial of the Holocaust, though. Not so with global warming denial, either.

These days, many scientists measure the warming of planet earth, which confirms the effect of the measured radiation properties and measured elevated concentrations of greenhouse gases. The temperature evolves in congruence with proven physics. Both cause and effect are evidenced by measurements, as is the case with plate tectonics.

The denial of global warming is not just a bit weird. It is excessively strange. Why was the debate settled in one case, plate tectonics, but not in the other two cases? Humans do not cause continental drift. In the other cases, humans were or are the cause. The difference is the negative human involvement, the element of guilt.

If it is asserted that guilt rejection favors the denial of the Holocaust, it may be objected that its deniers were not responsible for the wrongdoing themselves, which is of course true. Their parents were responsible or their grandparents, or the former’s or the latter’s friends or compatriots, or someone else with the same or a similar political orientation —or just another human being did it or failed to counteract the crime. It doesn’t have to be precisely guilt, or felt shame for oneself, that causes denial. It may be anything that negatively impacts on one’s own self-esteem through negatively impacting on human self-esteem.

How far back in time can the wrongdoing be or how much dispersed in a large group can the responsibility be to negatively affect self-esteem or induce a feeling of discomfort, guilt or shame —and denial? We can look at another case of science denial to find the answer to that question.

Quaternary extinctions

Whenever the capable, well-armed and cooperative hunters of the species Homo sapiens found or conquered new land, they drove many animal species to extinction. Eurasia, the Americas, the many islands of the Pacific (every one of them), the islands of the Siberian arctic ocean, what are today New Zealand or Madagascar: Whichever scene you chose: Sapiens arrived. Animal species disappeared.

The later the invasion, the more skilled and better armed the hunters, the more thorough were the extinctions. Most manifestly affected was the megafauna, i.e. animals about the size of humans or larger. The tragedy —another tragedy of the commons— is sometimes referred to as the Quaternary extinctions.

True, nobody was there to photograph the slaughtering or count animals. Nobody was there to report on snow cover, precipitation or sunspots, etc., either. The evidence for the Quaternary extinctions is nevertheless overwhelming. But not only the evidence is rampant. Still, there is widespread denial of the Quaternary extinctions, even among scientists, but certainly in the public sphere.

At least two other hominid species (Neanderthals and Denisovans) were among the victims of Sapiens. This provides additional psychological reason to repress the facts on the Quaternary extinctions.

Many seriously proclaim that Sapiens mixed peacefully with Neanderthals or Denisovans. The remains of genes from our closest known relatives in the human genome suggest it, they point out. However, the small fraction of Neanderthal and Denisovan genes in humans really suggests otherwise —together with what historians and anthropologists know about territorial disputes and its outcome, rape associated with warfare or men violently raiding for women.

As far as non-human species are concerned, not the extinctions themselves are still being questioned. The human cause of it is! (Does that sound familiar?) To explain the Quaternary extinctions, climate change is invented over and over again, no matter how little plausible that theory is.

When it helps our self-esteem, climatic change was there. When it damages our self-esteem, climate change isn’t there. The human mind, its creativity and its capacity to be biased, is remarkably flexible. It is capable of making things up if it pleases its self-esteem. Not less impressive is the human mind’s capability to repress and distort facts if doing so comforts the mind and reassures the soul.

There can be little doubt, that the denial of Darwinian evolution is dominated by religious concepts and early indoctrination. Undoubtedly, ideology plays a part in climate denial, too, as is succinctly explained by Eugenie Scott —but put in perspective by recent research. Additionally, the denial of evolution might be reinforced because it negatively impacts human self-esteem, too.

Climate preaching impacts negatively on one group of the population who interprets the preaching as an accusation, feels offended and rejects it by denying the problem —and safeguards its self-esteem. Another group welcomes and follows the preaching superficially and also preserves its self-esteem.

Although not the same thing, for our purpose, it is practically impossible to distinguish between the avoidance of guilt and the preservation of self-esteem. An accusation, whether consciously perceived or subconsciously received, inevitably impacts on ones self-esteem. In the place of guilt, self-esteem could have been the central expression in this article.

It would be far beyond this article’s scope to try and cover all underrepresented issues in the field. But there are more problems related to climate denial and self-esteem and it is fitting to mention some here.

More on self-esteem

Electronic media and the media’s principled belief in balance permit would-be experts to communicate with real experts and even have public debates. It provides deniers with opportunities for impression management to enhance their self-esteem.

Related and more important in the context of this article: When climate scientists get much respect and attention for working on climate change and for communicating on it, other people, particularly other scientists and would-be scientists, have a psychological motivation to discredit the real climate scientists‘ work. It may be seen as a matter of envy. Or it may be seen as a matter of self-esteem. If I believe that someone who is smarter than I, or more successful than I, is wrong, my belief helps me to safeguard my self-esteem.

I think many prominent climate deniers like Richard Lindzen or Bjørn Lomborg may be affected by this bias. If the hypothesis is true, it may —among other things— explain the surprising abundance of climate deniers from other sciences, including sciences close to climate science, like geology or meteorology, who missed the train to work on global warming and to take the right side on it.

This hypothesis may also explain the surprisingly tenacious resistance against new scientific theories in general, like continental drift. Envy can be a positive driver in the scientific process if it results in ambition. But if envy results in condescendence or even vilification it is not a productive element in that process.

As with Ignaz Semmelweis, there would be a story to be told to illustrate the hypothesis. In brief: From about 1890 onwards, German physicist Philipp Lenard worked very successfully on cathode rays. In 1905 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work. This work and the apparatus he conceived were essential for the discovery of the electron and X-rays. However, disappointingly for Lenard, other scientists, Joseph John Tomson and Conrad Röntgen, respectively, were credited above him for the two discoveries. From 1900 on, Lenard worked on the photoelectric effect, again with great achievements. But, once again, another scientist would be awarded the greatest honors. Albert Einstein was given the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics, not for his outstanding masterpiece, relativity, but for explaining the photoelectric effect based on Planck’s quantum physics. Planck, received the Nobel Prize for 2018. This did not bode well with Lenard’s self-esteem. He, and other scientists spent much time and effort to reject Einstein’s theories and achievements, as well as Planck’s.

The rejection of relativity in the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany shares many traits with today’s denial of global warming, including ideology and the assertion of a conspiracy. Particularly in the case of Lenard’s denial of Einstein’s and Planck’s achievements, personal level competition and envy might have been at work.

Clive Hamilton pointed out in 2010 that climate change is rejected because it originates from the wrong side of the political spectrum, i.e. the other side. More recent research supports this view (Kahan, Lewis et al.).

But people accept or reject ideas and beliefs not only based on ideology and groupthink. They also reject them when they originate from what they consider the wrong person. For example, I know of people who reject everything proposed and discovered by William Nordhaus because they dislike this or that other piece of information originating from the Nobel Prize winning economist. Such a reaction is wrong and unhelpful. However, it is part of human nature.

As far as I know, although it is important, psychologists have so far not named this distortion of perception that could be called wrong-person bias. There is also the reverse analog, a right-person bias —paramount in commercial product marketing.

We climate communicators should avoid the trap of becoming the wrong person, when it can be avoided. We should try to communicate honestly, without exaggeration or deception. The claim that we could and should solve the climate crisis with individual voluntary consumer action is wrong and, I shall point out later, it may be perceived as a deception or manipulation.

For Philipp Lenard, relativity was not just wrong. It came from the wrong person, Albert Einstein, who won the big prize for having explained what he, Lenard, had failed to explain. And it came from a Jew. Lenard was among the first scientists to join the National Socialist party, at a time when the motivation for this move was likely ideology, not opportunism or necessity. Lenard’s arguments were often anti-Semitic —which, comfortably or uncomfortably, together with the observation that it is often difficult to keep motives apart, brings us back to the topic this section began with.

It may be guessed that Holocaust deniers are statistically inclined to belief in a just world. In view of the extreme injustice that the Holocaust was, they might prefer to deny the facts rather than revise their view of the world as a just one. The human psyche is complicated. Several biases may be at work to distort a piece of cognition.

A special bias for denial

The bias called just-world belief describes the human tendency to view the world as fairer than it actually is. This bias makes us believe, disproportionately, that people deserve what happens to them. There is a test to assess the degree to which selected people (i.e. participants of a psychological experiment) believe in a just world.

In 2010 scientists Matthew Feinberg and Robb Willer reported on two studies they conducted to determine specifically the influence of just-world belief on the denial of climate change. In their first study, participants who were told that climate change is practically unresolvable showed increased levels of climate denial, but only if they were strongly inclined to believe in a just world. If told that climate change can be resolved easily, denial in that same group was reduced almost equally significantly. Those on the other side of the spectrum of just-world belief were less affected by the messaging. They responded on both types of messaging with slightly but significantly reduced changes in their level of denial.

In the second study, one segment of the participants was primed with statements supporting or eliciting just-world belief. The complementary segment was primed with messages contrary to just-world belief. Subsequently both segments were confronted with dire statements about climate change, including one that elicited dramatically that innocent children would be hit. Finally, as in the first study, the participant’s level of denial of climate change was assessed. «Participants who were primed with just-world statements reported higher levels of global warming skepticism (…) than did those who were primed with unjust-world statements (…)», the scientists reported.

The combination of the studies lets the authors conclude that «dire messages warning of the severity of global warming and its presumed dangers can backfire, paradoxically increasing skepticism about global warming by contradicting individual’s deeply held beliefs that the world is fundamentally just.» (Feinberg and Willer, 2010)

A byproduct of the second study also deserves to be acknowledged. As part of the assessment of the level of denial, seven questions were asked, e.g. «How solid is the evidence that the earth is warming?» One of the questions was considerably different from the others: «Overall, how willing are you to change your current lifestyle in order to reduce your carbon footprint?» It is problematic to qualify a refusal to reduce one’s personal carbon footprint as climate denial. Fortunately, the researchers also thought like that, at least to some extent, and specifically focused on the pattern of replies to this question with respect to the other questions probing denial. They found that those primed with just-world belief refused to (state to be ready to) reduce their carbon footprint and that this reaction was fully mediated for by the increased induced level of denial through the induction of just-world belief.

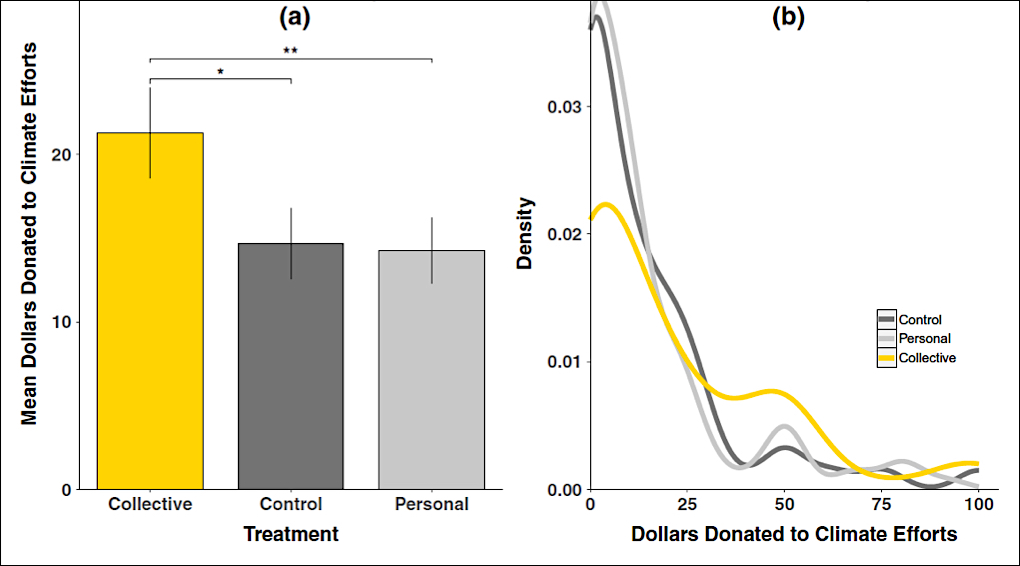

What, I dare to ask, if the low effect of climate preaching on the voluntary reduction of personal CO2-emissions could be explained by (fully mediated by, fully caused by, fully compensated by) the preaching’s induction of guilt and the rejection of it? What if the small acts of voluntary reductions by a small segment of the population due to climate preaching were entirely compensated for by less voluntary action in the other segments of the population because the preaching induces guilt and enhances the refusal to voluntarily make greener choices?

I do not claim that appeals for self-centered voluntary climate action, like personal carbon footprint reduction, negatively impact self-centered voluntary action itself, on average over all segments of a population. However, in the light of Feinberg and Willer’s results, even that possibility should not a priori be discarded. (This article, specifically its part 4, claims that climate preaching hampers rather than fosters progress on climate change overall, not just in the domain of voluntary consumer action.)

Feinberg and Willer studied the combination of dire messaging, just-world belief and denial, which is not the same combination as climate preaching, guilt induction and denial. However, it would be difficult to overlook the similarities. Belief in a just world and a desire not to feel guilty are connected via desirability or the respective bias.

There are more parallels between the studies by Feinberg and Willer and arguments made in this piece.

- First, the results produced by Feinberg and Willer show that the impact of climate messaging on climate denial may be very different for different groups.

- Second, the design of the two studies permitted to target the influence of specifically the just-world belief bias. However, the bias might, like so many other biases, be related to self-esteem because a just world, or an unjust world, is made what it is mostly by human activity —as a different climate is now made by human activity.

- Third, the belief in a just-world bias serves to justify free riding: There is no need to make the world a just place if it already is a just place. Climate change denial also serves as an excuse for inaction, i.e. free riding. (Actually, viewing beyond psychology, that is what climate change denial is all about.)

- Fourth, one departure point of Feinberg and Willer’s enquiry was this question: «But what if these appeals are in fact counterproductive?» The readiness to question the usefulness of habitual guilt-inducing climate communications was a precondition for the studies and their success.

- Fifth, but not least, dire messaging induces guilt. It augmented denial in one group but not in the other. Climate preaching induces guilt too. It augments denial in one group but not in the other, so it is argued in this article. Exposure to a climate message that portrayed global warming as a solvable problem —thus, less guilt induction or rather the opposite of guilt induction— decreased the level of denial regardless of the participants‘ belief in a just world («Positive Message» in the diagram below).

If there is distortion of cognition, one or more cognitive biases are at work. Many biases have in common that they play out if perception negatively impacts self-esteem. For this and other reasons, it is often difficult to keep the influence of various biases apart.

Moreover, feelings interplay with cognition. For example, it is difficult to imagine a message that evokes fear on climate change but does not also elicit guilt. And it would be difficult to quantify whether denial induced by such a message serves to avoid guilt or to repress fear.

The double bladed sword of fear induction

There can be little doubt that feeling fear has a superb potential to induce action. And it was discovered that fear makes us open minded insofar as it increases our readiness to consider varying pieces of information —which might help to counter denial. That is on one hand. On the other hand, it is almost ancient wisdom that fear can induce near total repression of danger in an individual if the cost of action is high or if the problem is believed to be bigger than the individuals capacity to resolve it. Not surprisingly, current wisdom on fear messaging on climate change can superficially be summarized like this: Its impact is rather negative, unless there is also hope as well as proximity, i.e. a perception of being immediately and personally at risk.

Practically, to elicit fear and hope at the same time is not easy. Fear-inducing messages tend to be dire and dire messaging discards hope, almost by definition.

Fear also increases social attitudes associated with the political right —or rather: security increases social attitudes associated with the political left. This was recently discovered by Jaime Napier and colleagues (Napier et al. 2018). And the political left rather accepts the science on climate change, while the political right rather denies it —albeit only very much so in western countries, according to another study.

Despite the complexity of emotional climate communications, and specifically fear induction, the debate over its up- and downsides progresses in the scientific domain. But there remains much confusion about it in the public and the media, as is explained by Lucia Graves in an article about the fear-piece by David Wallace-Wells in the New York Magazine, which «soon was the best-read story in the magazine’s history». Fear messaging about global warming, even if it is between implausible and absurd, is about as eagerly welcomed as is climate preaching.

Fear messaging and climate preaching also have in common that they suggest guilt and consequently induce rejection and denial in some people but may motivate others into action.

There is reason to believe that climate preaching induces denial more effectively than fear messaging, because climate preaching suggests more guilt, I suppose. There is reason to further speculate that fear messaging induces collective action, while climate preaching induces self-centered action —alas, that is what climate preaching aims at.

The study gap on guilt induction

One aim of this article is that the two-sided sword of guilt induction also gains the attention it deserves. But that would require putting aside the widespread a priori held belief that climate preaching is a good thing to do and should be well received.

My guess would be that people who are statistically much inclined to feel guilty about something (or people subjected to guilt induction), are either more likely than average to deny climate change (one segment of the population) or are more likely than average to respond positively to appeals for voluntary individual climate action (another segment) or do both: deny and respond positively to climate preaching. In contrast, I would expect those who are only weakly inclined to feel guilty (or were not made feel guilty through deliberate induction) to be only moderately inclined to deny climate change and moderately inclined to respond positively to climate preaching. In other words, I would expect climate preaching to cause denial and positive response, but more so among those who are inclined to feel guilty (or are made feel guilty as part of a study).

There may be other psychological factors or psychological predispositions which impact on denial as a consequence of climate preaching. Obvious candidates are: inclination to accept moral appeals; inclination to see them as an accusation; inclination to reject accusations; tendency to project one’s own guilt onto others.